In an international order based on norms and treaties to stop the proliferation of nuclear weapons, India stands as a disturbing exception. India, despite remaining outside the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), has access to civilian nuclear technology, nuclear trade and a fast-growing nuclear weapons program. This exceptional treatment is driven by geopolitical interests of major powers instead of rules within the non-proliferation framework, which threatens the credibility of the global non-proliferation regime and fuels the risk of instability in South Asia.

India’s nuclear journey started under the guise of peaceful purposes. In 1974, the first nuclear test of India, named Smiling Buddha, was conducted using the plutonium derived from the CIRUS civil nuclear reactor supplied by Canada and the US. India declared that the reactor would be used only for peaceful purposes. This violation of international norms led to the creation of the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) in 1975 to stop the diversion of civilian nuclear technology for military purposes.

The deal was first signed between India and the US in 2005, and India subsequently received the NSG waiver in 2008. This deal gave India the facility of trading in civil nuclear technologies, despite its refusal to join the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). India was allowed to retain various civil nuclear reactors outside the IAEA safeguards, which favoured India to exploit its civil uranium enrichment program for military uses. The 2008 NSG waiver pushed by the US and endorsed by many Western countries was politically driven and exceptional in its substance and implications. The rationale behind the deal was given that it would bring India closer to non-proliferation practices. The reality is different, as India only agreed to place 14 out of 24 power reactors under IAEA safeguards. India also produces fissile material for weapons, which is a key concern for arms control regulators. The 13-plus nuclear deals that India scored after the Indo-US nuclear deal, coupled with the NSG waiver, have also led the Indian domestic uranium material to be diverted for nuclear weapons. India’s nuclear arsenal has developed considerably.

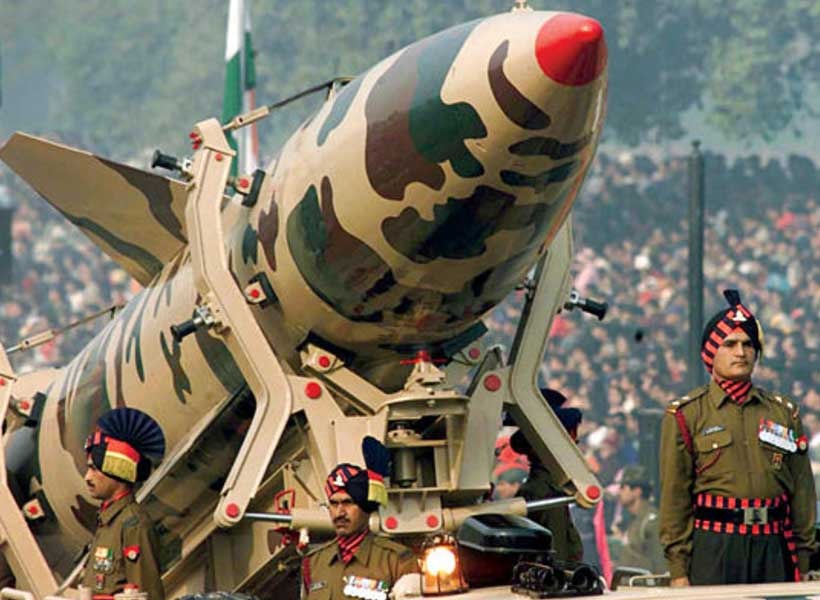

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), India has around 172 nuclear warheads. India is enhancing its nuclear weapons stockpile, focusing on technological advancements and strategic reach. For example, the expansion of the Agni V intercontinental ballistic missile with a range of over 5,000 km, efficient in hauling Multiple Independently Targetable Re-entry Vehicles (MIRVs), shows a trend toward more adaptable and active nuclear actions. The programme of Agni VI is back on track, while the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) is proactively working on the Submarine Launched Ballistic Missile (SLBM) variant. These developments indicate a doctrinal shift from minimum deterrence to credible counterforce.

India claims to follow a No First Use (NFU) policy; however, there is ambiguity in its commitment to this policy. The Indian officials who are committed to NFU, including Defence Minister Rajnath Singh, stated that however, what happens in the future would depend on the circumstances. “In any event of a central attack against India, or against the Indian forces by chemical or biological weapons, India also retains the option of attacking with nuclear weapons.” India’s adoption of the Cold Start Doctrine (CSD) and aggressive adventurism possibilities towards Pakistan further increase mutual distrust and sabotage Pakistan’s attempts towards arms control and conflict settlements in South Asia. India’s CSD is a destabilising strategy for launching a sudden conventional strike under the nuclear threshold. It increases the risk of conflict, and therefore, it is countered through Full Spectrum Deterrence (FSD), which includes tactical nuclear weapons. These policies undermine deterrence in South Asia. The region faces a volatile environment where any potential crisis can escalate rapidly due to preemption and misperception.

The states in the global nuclear order are often treated on the basis of US perceptions of partners, allies and adversaries. Due to India’s US strategic partnership in the Indo-Pacific, it receives special treatment from the US. On the other hand, countries like Turkey and Iran, which are not US allies, suffer more scrutiny and no favourable treatment. For example, Iran, despite signing the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), which the US unilaterally terminated, faces severe sanctions for its nuclear activities. On the contrary, India obtained access to nuclear technology without signing the NPT. These double standards destroy faith in the rule-based global nuclear order. Furthermore, Turkey was subjected to CAATSA sanctions for purchasing the Russian S-400 system and was removed from the F-35 program. In comparison, India, on the same deal, received a US waiver due to its strategic role in countering China.

Similarly, global geopolitical competition between the US and China has shaped strategic decisions like the NSG waiver. According to the report of the Congressional Research Service, the US supports India’s nuclear programs for a broader strategy to counter Chinese influence in Asia. Western allies and the US have emphasised strategic alliances over non-proliferation norms. This temporary strategic calculus might yield geopolitical gains, but it has a long-lasting cost for the international nuclear order. IAEA, NSG and other non-proliferation frameworks needs to be revisited. India should place all its civilian programs under the safeguards of the IAEA. In this era where arms control is deteriorating and the new technologies are threatening nuclear thresholds, the world cannot afford such nuclear exceptionalism. The Indian nuclear exceptionalism threatens to reverse decades of development and sets an unsafe precedent for future proliferation. India’s 1974 nuclear test, by using diverted civilian technology, raised critical proliferation concerns and yet India received an NSG waiver in 2008, despite being outside the NPT. This represents a double standard, which undermines the nuclear order as well as regional stability.

This article was published in another form at https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2025/08/15/indias-nuclear-exceptionalism-an-irony-a-question-to-non-proliferation-framework/

Shahwana Binte Sohail is is Research Assistant at the Centre for International Strategic Studies Islamabad.