Abstract: This article examines how Rudra Brigades operationalise India’s evolving Dynamic Response Strategy by integrating speed, precision, and jointness at the brigade level. It situates these formations within India’s broader theatreisation and force-restructuring agenda, as validated through recent exercises and operations. The analysis highlights how this shift compresses warning times, expands conventional response options, and alters crisis dynamics in South Asia. For Pakistan, the emergence of such high-readiness formations underscores the need to adapt deterrence, force posture, and crisis-management mechanisms to a changing regional security environment.

Bottom-line-up-front: India’s Rudra Brigades reflect a shift toward faster, modular, multi-domain conventional options that compress crisis timelines and lower the practical threshold for limited military action in South Asia.

Problem statement: How is India’s transition from mobilisation-dependent forces to ready, terrain-tailored formations reshaping the logic of limited war?

So what?: Pakistan must improve conventional deterrence, invest in counter-multi-domain capabilities, and push for bilateral crisis-management mechanisms to adapt to India’s evolving force posture and prevent rapid escalation.

Introduction

India’s shift from heavy, mobilisation-dependent formations to ready-in-place, modular multi-domain brigades is introducing a new risk for the region. This shift began to crystallize after the mid-2010s, and subsequently gained urgency after back-to-back crises with Pakistan in 2019 and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 2020, and has taken practical form since 2022 through the conversion and testing of new integrated formations such as the Rudra Brigade. The rise of Rudra Brigades sits at the centre of this transition.[1] These new formations are designed to move fast, integrate multiple combat arms, and deliver calibrated force under India’s Dynamic Response Strategy (DRS).[2] India’s Exercise Trishul conducted, so soon after Operation Sindhoor was “paused,” signals that New Delhi is not walking away from large-scale conventional options.[3] Instead, it is refining them into more agile, politically viable tools. For Pakistan, this reorganisation not only compresses warning times but also broadens the range of conventional options India can employ to complicate crisis management under the nuclear overhang.

What Are Rudra Brigades?

Rudra Brigades represent the most significant structural change in the Indian Army since the idea of the Integrated Battle Group entered official debate.[4] The Indian reports describe them as all-arms formations that permanently integrate infantry, armour, artillery, engineers, air defence, electronic warfare elements, drones and logistics under a single brigade-level command.[5] Unlike traditional brigades that rely on attachments during wartime, these formations are constructed as self-contained units in peacetime. The plan is to convert the Indian Army’s some 250 single-arm brigades to ensure that India has combat groups that are already organised, trained and equipped to conduct swift, tech-enabled, flexible operations without assembling additional troops.[6]

These brigades are likely to be configured to match the terrain in which they are expected to deploy and fight.[7] This tailoring reflects a shift toward limited-war concepts that emphasise theatre-bound offensive action by forward-deployed, terrain-optimised forces rather than general-purpose manoeuvre formations. In Ladakh, Rudra Brigades would be infantry-dominant, supported by high-altitude mobility, light artillery, and persistent drone-based surveillance to secure ridgelines and retain the ability to launch shallow, limited offensives across the Line of Actual Control. In Sikkim, where operations are constrained by narrow valleys and steep gradients, these formations would prioritise infantry and artillery capable of manoeuvring and delivering precision fires across broken terrain, combining forward defence with the option of limited cross-border action into Tibet to disrupt adversary deployments. In Jammu and Kashmir, by contrast, Rudra Brigades would be structured for faster concentration and offensive manoeuvre, defending in place during routine tension while remaining postured to conduct calibrated attacks across the Line of Control or International Border.

Along the western plains and desert areas, these concepts would translate into armour-heavy groupings built for space-centric operations, utilising mechanised infantry and self-propelled artillery to achieve sharp, swift spatial gains. Conversely, along the Line of Control, the focus is shifting toward techno-centric warfare, where infantry and Special Forces leverage sophisticated ISR and space-based surveillance to execute precision punitive responses within the increasingly complex Grey Zone of the border. This theatre peculiarity is a deliberate move away from traditional brigades toward combat modules tailored to a specific operational environment. The reported presence of Rudra Brigades in Ladakh, Sikkim and Rajasthan show that the Indian Army is applying this concept on the full front, signifying a desire to institutionalise rather than experiment with the model in areas likely to face crises.[8]

The integration and customisation outlined above indicate a shift in the Indian military’s thinking. The conceptual shift from the previously used Cold Start Doctrine to an agile, probing Cold Strike posture is explicitly anchored in the Rudra model. The Cold Start Doctrine emerged in the mid-2000s as India’s attempt to create space for swift, limited conventional military operations against Pakistan under the assumption that such actions could be conducted below Pakistan’s nuclear thresholds. It envisaged the swift mobilisation of integrated strike formations to conduct limited, shallow offensives within a compressed timeframe. Cold Strike is seeking a different paradigm, where Cold Start relied on the mobilisation of massive strike units, a process that proved far too slow to achieve any strategic advantage. Cold Strike seeks to capitalise on small, high-readiness, multi-domain formations that can conduct precision operations without necessarily mobilising division-sized groups. It integrates air power, precision strikes, and high-readiness ground units to generate rapid effects. The deployment of the Rudra Brigades realises this conceptual change. They integrate all relevant arms under a single command, enabling India to project a calibrated force from the first hours of a crisis. The shift is from “mobilise then strike” to “strike while mobilising,” which is the essence of India’s new operational logic. Exercises such as Akhand Prahar have demonstrated this clearly, where a Rudra Brigade used drone-assisted targeting, coordinated manoeuvre and integrated fires in real time.[9]

Rudra Brigades and India’s Theatre Command Vision

India’s theatre command reforms remain sensitive and formally incomplete.[10] Yet, at the organisational level, the Armed Forces are already assembling key building blocks, including Rudra Brigades, emerging Bhairav battalions, the rollout of Ashni drone platoons, and stronger joint command-and-control links for ISR, air support, and electronic warfare.

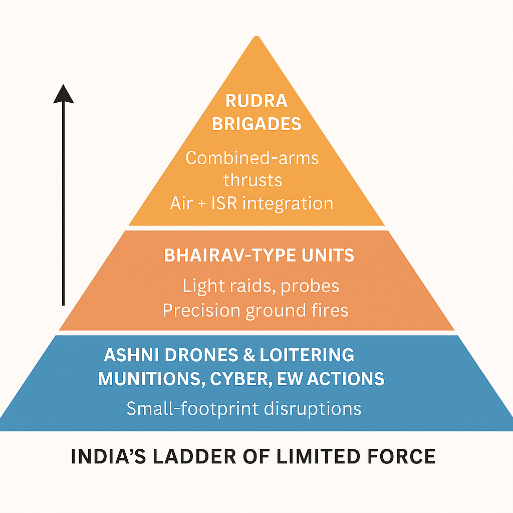

They operate alongside two other types of formations that have appeared in recent years. One is the Bhairav battalions, which are light, terrain-familiar commando-infantry units raised for rapid border action and raiding tasks.[11] Similarly, Ashini drone platoons are being rolled out across infantry battalions, providing organic surveillance and loitering munition strike capacity. Rudra provides the manoeuvre and combined-arms punch. Bhairav gives a light, fast, raiding edge.[12] Ashni saturates the local airspace with cheap, persistent sensing and strike options along with improved accuracy and situational awareness. Together, Rudra, Bhairav and Ashni, though still in early stages, would form a modular force package that can be worked into any future theatre command.

Exercise Trishul offered a preview of how this architecture may work in practice. The exercise brought together tri-service elements across Rajasthan, Gujarat and the Northern Arabian Sea. Within it, the Akhand Prahar sub-drill saw XII Corps validate its Rudra Brigade and Bhairav Battalion in a drone-dense, electronic warfare-heavy scenario with close air support and heli-borne operations.[13] The way these units were employed reflected not only a desire for tri-service synergy but also an attempt to rehearse the command relationships and effects-based planning that a Western Theatre Command would need.

Rudra Brigades are also the organisational instrument through which India can give practical form to its Dynamic Response Strategy (DRS). It seeks to provide the political leadership with a graded ladder of conventional responses. These range from drone strikes and limited artillery punishment to battalion-sized raids and brigade-level thrusts. None of this is new in conceptual terms. What is new is the attempt to embed this ladder in pre-integrated, high-readiness formations. Thus, the Rudra Brigades make DRS executable.

Implications and Way Forward for Pakistan

For Pakistan, the emergence of Rudra Brigades and the broader ecosystem around them raises at least four serious concerns. First, warning time is reduced. When combined-arms units with organic enablers are integrated and exercised together in peacetime, they can transition from political authorisation to execution with minimal additional force assembly. This compresses the decision-to-action cycle by reducing reliance on visible mobilisation, last-minute inter-service coordination, and large logistics movements that traditionally generate warning. Pakistan’s military and diplomatic responses must therefore operate within a shorter window, limiting opportunities for signalling, dispersal, and third-party mediation before action unfolds.

Second, the bandwidth of Indian conventional options expands. The recent May 2025 crisis quickly climbed the escalation ladder, but this will give India more rungs to climb. At the lower end, there are Ashni-enabled drone and loitering-munition strikes, cyber and electronic operations, and limited cross-border actions by Bhairav-type units. At the higher end, Rudra Brigades can deliver short, sharp combined-arms blows under air cover and ISR support. Together, these capabilities make it easier for New Delhi to believe that it can “do something” militarily without breaching Pakistan’s nuclear threshold.[14]

Third, nuclear-conventional entanglement deepens. Multi-domain operations seek to generate converged effects across domains, often by contesting an adversary’s sensing, communications, and decision-making processes, rather than relying solely on physical destruction of forces. Many of these are dual-use or intertwined with assets that also play roles in nuclear command and control. In a crisis, India’s attempts to blind or disrupt Pakistan’s conventional systems could be misread as preparatory steps for counterforce operations. This increases the risk of worst-case threat perceptions and inadvertent escalation.

Fourth, crisis management becomes more difficult in an environment where Operation Sindoor is paused but not formally terminated, leaving India’s Armed Forces in a semi-mobilised posture. The presence of high-readiness, modular formations like Rudra means that military options will appear more usable and more tempting inside the Indian system. This is especially dangerous in the aftermath of terrorist incidents or political shocks, when public pressure to respond is high and decision time is short.

Way Forward

The main problem for Pakistan does not lie in the existence of such brigades, but in the logic they represent within a system-wide approach. By reducing mobilisation requirements and embedding key enablers within peacetime formations, Rudra Brigades increase the practical usability of conventional force. Military studies consistently show that when force structures are designed for rapid, modular employment, political leaders have a wider range of actionable options. The repeated validation of such formations in exercises like Trishul suggests that India is seeking confidence in conducting short, theatre-bound operations rather than relying solely on infrequent, large-scale campaigns. For Pakistan, this does not imply the inevitability of conflict, but it does indicate a higher risk of crises emerging more quickly, evolving along multiple escalatory pathways, and offering fewer clear exit points.

Pakistan has to respond to this trend by further enhancing its multi-pronged strategy that includes, but is not limited to, the deployment of high-tech counter-unmanned aircraft systems (UAS), electronic warfare, enhancing the integration of intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR), air defence and corps-level firepower, and development of its own agile and technology-enabled response formations. In this regard, recent developments, such as the establishment of the Pakistan Army Rocket Force Command and changes in the military structure, are in the right direction.

There is also the need to invest in effective crisis-communication channels. With respect to Pakistan, New Delhi should seriously consider steps to reduce the risk of misperceptions and miscalculations. It is important to realise that India is moving to a different posture for warfighting.[15] With New Delhi embracing the concepts of modular, ready-to-fight, and multi-domain units, built to operate in specific terrain and integrated into a cohesive theatre concept, South Asian crisis dynamics will change. Pakistan’s preparedness will depend on understanding this shift early and adapting its own posture accordingly.

Endnotes

[1] Vivek Kumar, “Rudra, Bhairav All-Arms Brigades to Boost Army’s On-Ground Capabilities in Border Areas,” India Today, July 26, 2025, https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/rudra-bhairav-all-arms-brigades-to-boost-armys-on-ground-capabilities-in-border-areas-2761813-2025-07-26. [2] Ali Mustafa and Rabia Akhtar, “India’s Evolving Military Options and the Logic of Dynamic Response,” The Diplomat, March 18, 2024, https://thediplomat.com/2024/03/indias-evolving-military-options-and-the-logic-of-dynamic-response/. [3] Press Information Bureau, Government of India, “Indian Army Conducts Exercise Trishul to Validate Integrated Multi-Domain Operations,” press release, November 2025, https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2189935. [4] “Integrated Battle Groups (IBGs): India’s New Warfighting Concept,” StudyIQ, accessed December 22, 2025, https://www.studyiq.com/articles/integrated-battle-groups/. [5] “Army Forms Rudra Brigade for Multi-Domain Operations,” The Times of India, November 2025, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/jaipur/army-forms-rudra-brigade-for-multi-domain-operations/articleshow/125283447.cms. [6] P. C. Katoch (Lt. Gen., Retd.), “Rudra Brigades & Bhairav Commando Units,” SP’s Land Forces, August 14, 2025, https://www.spslandforces.com/experts-speak/?id=1302&h=Rudra-Brigades-and-Bhairav-Commando-Units. [7] Sushant Sareen, “Rudra Brigades: A Doctrinal Shift for Fighting in a Multi-Domain Environment,” CS Conversations, 2025, https://www.csconversations.in/rudra-brigades-a-doctrinal-shift-for-fighting-in-a-multi-domain-enviornment/. [8] Indian Army, Land Warfare Doctrine – 2018 (New Delhi: Indian Army, 2018). [9] Firstpost, “Rudra Brigade: Inside India’s New Integrated Warfighting Plan | Vantage with Palki Sharma | N18G,” YouTube video, accessed December 22, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fc58r22yetI. [10] “What Is Operation Akhand Prahar? Rudra Brigades and Prachand Manoeuvres Signal a New Era for Indian Defence,” The Economic Times, November 2025, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/what-is-operation-akhand-prahar-rudra-brigades-prachand-manoeuvres-signal-a-new-era-for-indian-defence/articleshow/125269853.cms. [11] Snehesh Alex Philip, “Theaterisation Reform Is Stuck on Ranks and Roles,” The Print, September 2025, https://theprint.in/opinion/theaterisation-reform-is-stuck-on-ranks-and-roles-india-military/2750307/. [12] WION, “India’s Rudra Brigade: New Doctrine, New Force Structure Explained,” YouTube video, accessed December 22, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sR2h9ayH8R4. [13] “Army Equips 380 Infantry Battalions with Ashni Drone Platoons,” The Economic Times, October 2025, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/army-equips-380-infantry-battalions-with-ashney-drone-platoons/articleshow/124744881.cms. [14] “Fast, Furious, and Future-Ready: Why the Indian Army’s Rudra Brigade Could Be a Game-Changer Against China and Pakistan,” The Economic Times, August 2025, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/new-updates/fast-furious-and-future-ready-why-indian-armys-rudra-brigade-could-be-a-game-changer-against-china-and-pakistan/articleshow/122944381.cms. [15] Nishank Motwani, “No War, No Peace: India’s Limited War Strategy of Controlled Escalation,” The Diplomat, June 2025, https://thediplomat.com/2025/06/no-war-no-peace-indias-limited-war-strategy-of-controlled-escalation/.Syed Ali Abbas is Research Officer & Comm Officer at the Center for International Strategic Studies (CISS) Islamabad. He is also an MPhil scholar in the Department of Strategic Studies at the National Defense University (NDU) Islamabad.